The Making of “Making Modern America”

In this blog post, Philbrook’s Chief Curator Catherine Whitney explores the big ideas behind Philbrook’s upcoming show, “Making Modern America.”

PROGRESS, ENERGY, AND POWER were buzz words during America’s modern age—a vibrant period characterized by rapid change and industrial growth nationwide.

Big cities like New York, as well as urban centers like Tulsa, flourished in this post-World War I cultural environment that celebrated technology, machinery, and modern styles in art and architecture.

Russell Lee, “Winch Operator, Oil Well, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma,” 1939

Rural areas were likewise transformed as rails, roads, and powerlines crisscrossed the country. Factories and refineries joined shipyards and granaries to alter the look of America with man-made landmarks.

Progress promised a better tomorrow, but it also began to stir growing fears. What were the unseen threats that industrial expansions posed to the natural environment–once considered America’s pristine symbol of promise and collective pride–and how might society be changed for better or worse?

Making Modern America examines this paradox of progress through the lens of American industry. It presents the many complex–and often conflicting–ways artists working from 1910 to 1960 portrayed the social and environmental changes taking place during the making of modern America.

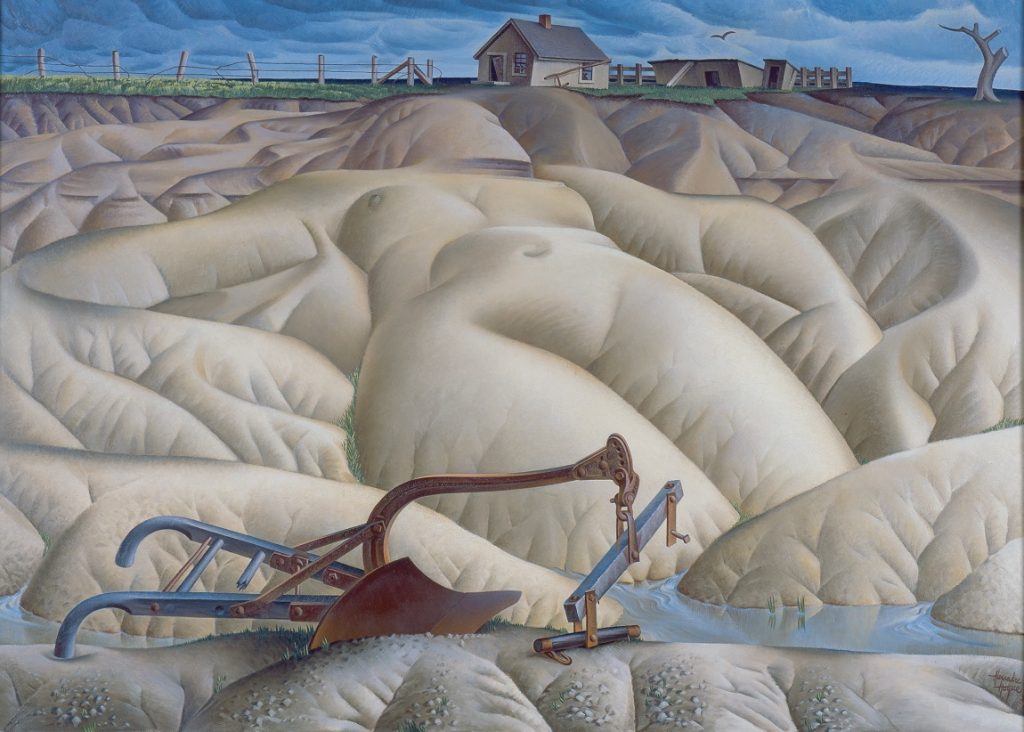

Alexandre Hogue, “Erosion No. 2 – Mother Earth Laid Bare,” 1936

While many of the paintings, photographs, and prints on display optimistically celebrate industry with avant-garde or regional styles, others reflect the social and environmental impacts that began to weigh heavily upon the national psyche and the natural environment, particularly during and after the Great Depression.

Iconic artists such as George Bellows, Charles Sheeler, Thomas Hart Benton, and Jacob Lawrence are joined by less-established names like Lucienne Bloch, Eldzier Cortor, and Doris Lee in a thematic presentation across four main sections that consider the rise of the modern city, industrial power, labor, and social and environmental impacts.

Geometric abstractions and soaring views of bridges, skyscrapers, and urban streets populate The Mighty Metropolis section, calling attention to new perspectives in painting and photography, as well as modern marvels of architecture and engineering.

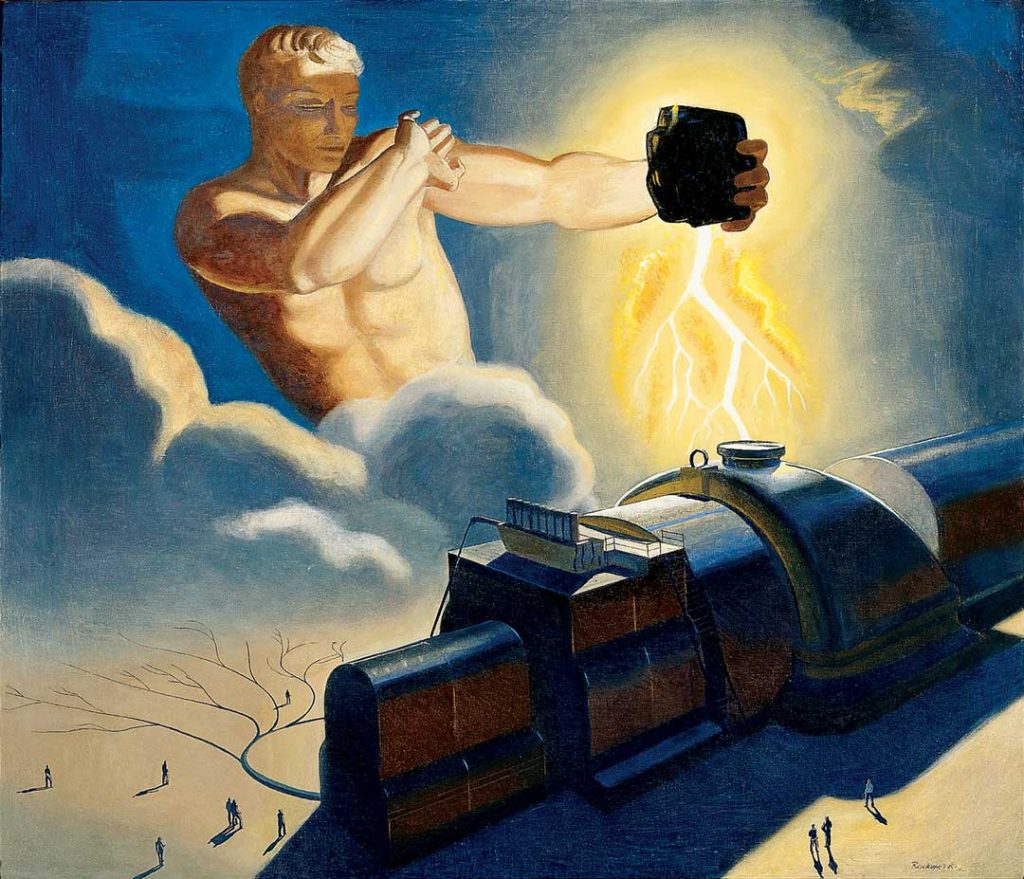

Industrial Power looks at the spread of electricity, power lines, and oil exploration over the landscape as well as the ways in which industry began to influence artists directly through commissions and corporate collections.

Heroic Labor examines popular concepts of work and masculinity from the 1920s and ’30s, as well as ways these portrayals changed during times of economic hardship and war.

The exhibition’s final section, The Paradox of Progress, considers how industrial advances transformed the social and natural landscape of America and continue to do so today.

National and regional loans from museums including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, enrich an exhibition that was originally inspired by Philbrook’s own Standard Oil Company Collection, given to the Museum in the 1950s. Standard Oil commissioned artists to document the oil industry’s contributions to the war effort during World War II, toured these works in regional exhibitions, and reproduced some of the images in their company magazine. These and other industry-inspired works such as Rockwell Kent’s Endless Energy for a Limitless Living (Dayton Art Institute), contrast with views by socially minded artists of the 1930s to the 1950s, many of whom scrutinized America’s earlier, optimistic embrace of the new against the considerations of a blighted landscape, a personal hardship, or an affected community.

Rockwell Kent, “Endless Energy for Limitless Living,” 1945-1946

In addition, everyday objects of industrial design from the Tulsa Historical Society will populate the presentation to illustrate how then-popular principles of efficiency, speed, and streamlined design affected art and everyday life, particularly during the art deco era.

These diverse perspectives, portraying both the attraction and the alarming power of progressive enterprise during the first half of the last century, form the collective view of this show and continue to inform our ongoing dialogues about progress, energy, and growth in America.

See “Making Modern America” at Philbrook Museum of Art. On view February 10 – May 26.

Image credits:

Russell Lee, Winch Operator, Oil Well, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, 1939 Gelatin silver print, 11 x 14”. Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Museum purchase, 1983.1.42.

Alexandre Hogue, Erosion No. 2 – Mother Earth Laid Bare, 1936. Oil on canvas, 46 x 61 ½ x 2 ½”. Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Museum purchase, 1946.4.

Rockwell Kent (American, 1882-1971), Endless Energy for Limitless Living, 1945-1946. Oil on canvas, 44 x 48”. The Dayton Art Institute, Gift of Dane and Kerry Dicke, 1994.60.